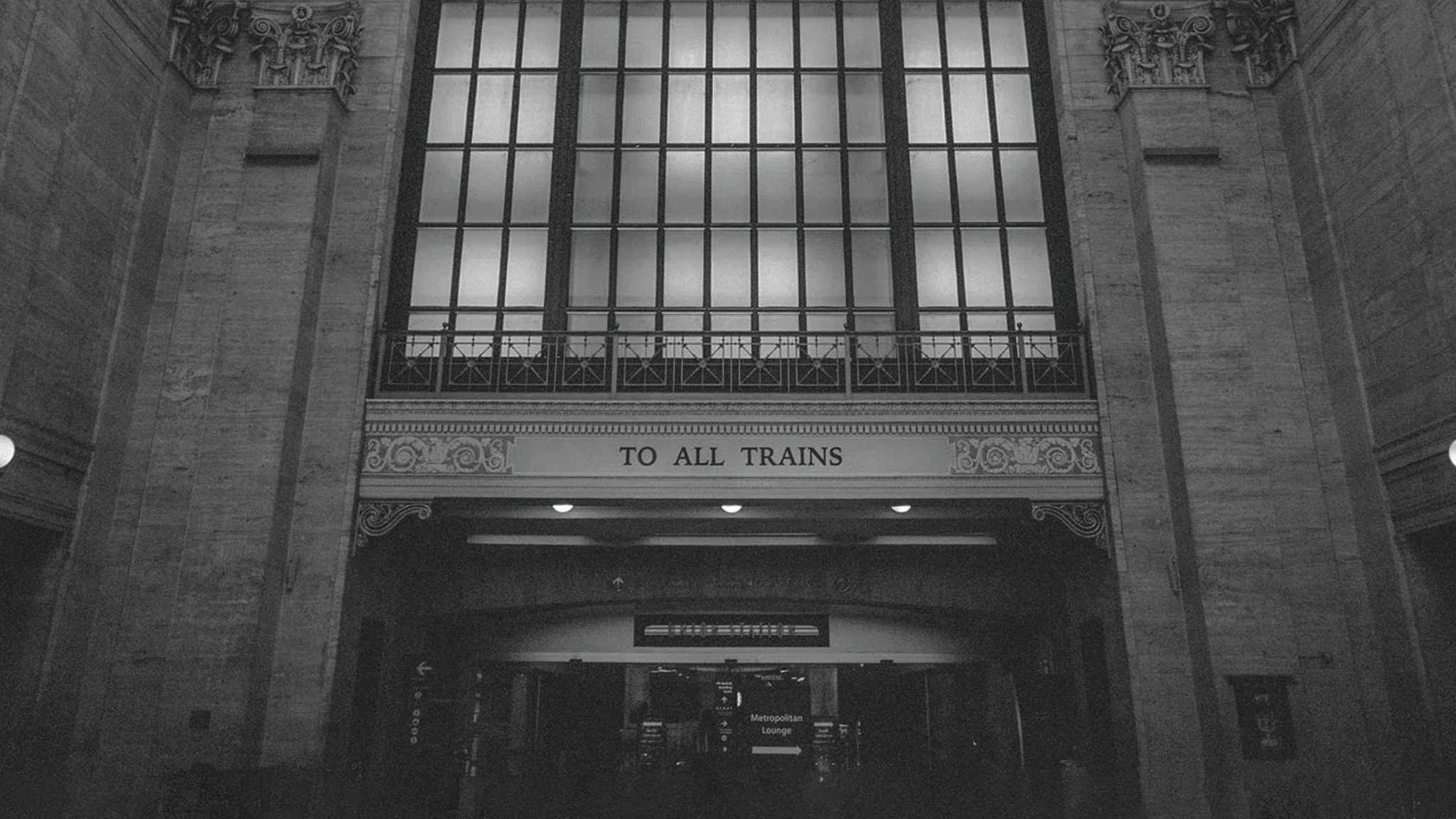

Less is More: Shellac’s - To All Trains

It wouldn’t be appropriate to talk about the new Shellac record without honouring the tragic passing of Steve Albini, esteemed producer, musician, and frontman of the band Shellac, to whom this review is dedicated. Since the release of 2014’s Dude Incredible, the band has been silently working on this album, while occasionally still doing live performances. Because of Steve Albini’s passing from a heart attack, the band have decided to put out the record as is, preserving the final recording they have as a trio.

As a whole, Shellac has changed up their sound throughout their three decades of being a band, but the most notable change has been them moving away from their noisy and raw roots. For a man like Albini, whose career has been defined by raw and aggressive rock through bands such as the short lived but incredibly important Big Black and the very ill-named Rapeman, it’s hard to associate his work with a well produced sound. However, as their newest and possibly last record, To All Trains, shows, this absolutely doesn’t hold them back from their aggressive and cynical sounds that have defined their entire career.

One consistent sound throughout Shellac’s discography is their ability to make repetitive songwriting and riffs work, which you would expect from a band that describes themselves as a "minimalist rock trio." Listening to their 1994 record At Action Park, you could still pick up hints of slower, more drawn-out songwriting through tracks like Song of the Minerals and The Idea of North. These songs showed that Shellac was excellent at keeping a groove with their riffage rather than just using pure aggression to get their energy. This is best exemplified on To All Trains’s opening track, WSOD, which kicks off the album with a bluesy sound as the trio lock into a groovy rhythm. By the time Albini starts singing, half the song is already over, which demonstrates one of the best and worst aspects of this album. Due to the fact that the album was released early, the tracks themselves are considerably shorter and underdeveloped, which explains why the record is the shortest out of all of their discography. However, Shellac shows how even in short songs, they are still incredibly concise and manage to make a song seem fully fleshed out.

Tracks like Scrappers, Chick New Wave, and the incredibly bleak Days are Dogs show this well, where Albini’s abstract writing and the band’s repetitive songwriting help to create songs that sound closer to pessimistic vignettes than half-baked ideas. However, this can’t work every time, such as in the track Scabby the Rat, which does end up feeling incomplete and unsatisfying (but still fun). The songs that are fully developed end up with Albini cryptically rambling about a topic or his cynical feelings, which is pretty par for the course for a Shellac song. Songs like “Tattoos” and “How I Wrote How I Wrote Elastic Man (Cock & Bull)” show how oftentimes, what makes Albini’s music work is how he conveys his lines rather than what he is saying, which has always been something that I like about his music and in the general noise rock sphere of music. The exception to this is the song Wednesday, which is about a man who takes his own life because nobody bothered to talk with him about the burdens he was carrying, perfectly highlights the bitter core at the heart of the band that defined them, in its most direct and unflinching way.

The last track of the album, “I Don’t Fear Hell”, is the best song on the record and the most important song regarding why the album exists. The song is about Albini boldly saying that he isn’t afraid of the afterlife because he knows he’ll be in good company. For a man who’s dedicated his life to being with and helping the underground, regardless of whether they would end up successful or are now forgotten in the annals of time, his final statement that he would rather remain with the unknown and the feared because that’s what he has always been more comfortable with is a perfect final tribute to him not only as an artist and musician but as a person. The song is also amazing musically, with the band returning hints of their former raw energy with their newer, slower style, creating a song that has a lasting impact. The song ends with them drawing out the riff at its most minimal. This isn’t the first time they’ve done this in their songs. “House Full of Garbage” from 1998’s Terraform had a very sparse drum solo in the last minute of the song, and “Genuine Lulabelle” from the brutally underrated 2007 record Excellent Italian Greyhound has an incredibly experimental spoken word segment in the middle of the song. While the effectiveness of it really depends on where it’s used on the album, “I Don’t Fear Hell” manages to capture the spirit of the band by keeping the audience in suspense before ending in one last crescendo, a perfect way to end the album and possibly their careers.

Of course, I could be reading too much into these songs. After all, Steve Albini did say once that his first Shellac album was all about baseball and Canada, so who knows if these songs are all just really elaborate symbolism for the next Chicago Cubs winning the World Series or Trudeau winning the next election?